Miriam Rudolph’s work has a sense of urgency in it’s beautifully layered and patterned narratives. Her show leaves you thinking about our own place in these narratives of our planet.

I had a chance to ask Miriam a few questions about her work.

Can you tell me a bit about your work and the environmental and activist themes you were exploring?

disPOSSESSION is an exhibition that explores the accumulation of wealth of few and the displacement of many with a focus on the expansion of soy and beef production in Paraguay, ensuing environmental, social, and economic consequences, as well as connected indigenous land rights and peasant food sovereignty issues. In my artworks, I explore the disappearance of the dry forests of the Paraguayan Chaco due to deforestation, the idea of enclosure as a symbol of privatization and capitalist systems, the struggle to maintain diversity through seed saving traditions in the face of expanding monocultures, and the displacement of local populations due to land grabs.

I grew up in Paraguay, South America. My life and my thoughts are forever linked to that beautiful and complicated place. I was raised in a socially complex setting with a colonial past and present in which European/Canadian settlers live next to indigenous communities, landless Latino peasants, and large estates owned by Paraguayan elites or, increasingly, by international investors and transnational corporations. Living standards, access to land, food, and education, as well as interests in land usage vary widely between the different groups. From this experience of unequal and unjust distribution of wealth and access comes a desire to bear witness and contribute to a dialogue on such issues as cultural change, sustainable farming and the environment, dispossession and migration, and food sovereignty.

Your work is very narrative, can you tell me a bit about the stories you are telling in your work?

Through printmaking, I am building a visual narrative that not only analyzes but also embodies the issues I am addressing. In some of my prints, for example, I layer printed images over and over again to build up large-scale imagery that dwarfs smaller counterparts to portray power relationships. In other instances, I print on both sides of a translucent Asian paper, allowing the paper to embody a physical barrier between the past and the present. Demarcations of plate marks subtly reference enclosure or the gridding of land surveying. In another series, I explore the imagery of lightly etched figures of men, women and children, fences crossing the entire image, and detailed drawn sections of dense forest printed upside-down and disappearing off the edge of the paper. The translucency of the figures suggests a lack of presence, either a distant past or a disappearing future, while the other components of the image suggest separation or enclosure and the disappearance of the dry forests, an inversion of the natural order. I keep the titles of my works short and straightforward to give the viewer a key to enter the image’s narrative.

Can you tell me a bit more about your process in composing your prints and how you create the work?

My methodology consists of gathering research materials, such as essays, articles, documentaries, literature, satellite imagery, personal testimonies and observations, and using them as layers of information in my artworks. I work with both scientific and empirical knowledge. I then try to figure out how to translate what I have read and heard into images that will carry the content I am trying to convey and that will draw the viewer in. In my etchings I have developed a process that takes advantage of the reproducibility and repetition of printing plates to achieve a complex build up of images that mirrors the multi-layered narratives involved in these issues. I have created a library of etched plates that I utilize as drawing tools to build up the imagery freely and intuitively on the sheet of paper, while maintaining control over the narrative content.

The physical and chemical process of leaving marks on the surface of a copper plate by etching it in acid lends itself remarkably well to my narrative imagery, allowing me to edit and layer the images. After making proofs, I can re-work and re-etch the printing plates, before inking them up, wiping the surface clean again, and running them through a manually operated printing press to transfer the image onto a damp sheet of paper. It is a very labour intensive process, but I love the subtleties and the variety of mark making I can achieve through etching. I can make highly detailed drawings, such as the forests and traditional gardens I have drawn using a steel needle, or I can brush loose washes of ferric chloride onto the copper to etch the clouds. These more general, abstracted marks carry emotion; they create a melancholy and ominous mood in the images. The clouds were a way for me to express a form of power, corporate power or market power that I could never quite seem to pinpoint or humanize in my readings. While my work is melancholy and dark, it is also beautiful. I’m trying to draw the viewer in, to seduce the viewer to step closer and then engage with difficult issues.

What can viewers expect to see?

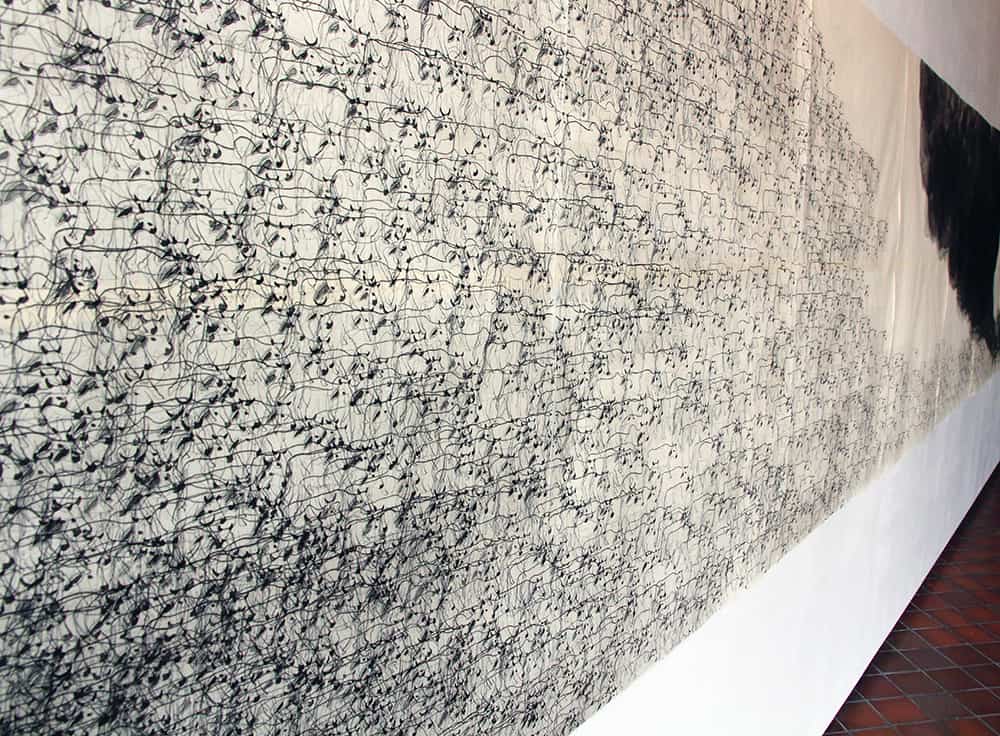

In the gallery there are four separate spaces, each representing a part of the narrative. There is one space with more traditional prints that connect to each of the issues I talk about. Then there are also three larger print installations. The form of each print installation is important to carry its content. Colonization by Cattle, for example, is presented as a panorama built from multiple panels of Asian paper to portray the epic proportions of this ongoing linear narrative. The herd in its sheer number of cows and in its scale overwhelms the small remaining forested section. While on one level the herd appears quite threatening in its scale, the cows are drawn in an almost gentle or benign way, since in reality they are innocent participants, or even victims, in this expansion of meat production.

The Soy Field and The Garden, consisting of a grid of 146 paper tiles pasted on the wall, form a fragmented vision of the land impacted by industrial agriculture. I combine my own grid with satellite imagery of regions in the Chaco where soy plantations are cropping up. I again work with layers of imagery to portray a kind of take-over by the soy plants of the land. The scale of the whole piece also gives a sense of that take-over through its overwhelming size, encroaching on the one remaining traditional garden. On some of the tiles I’ve printed a more mechanical pattern of plants to reference the engineered monocultures. On other tiles I’ve printed a red droplet pattern to refer to the repeated application of toxins that fall on the land and seep into the ground.

Seeds of Hope is a free hanging banner suspended above ceramic seed jars that hold the sacredness of life embodied in a seed. The vertical triptych invokes a gesture of blessing from above for the labour of planting and the traditions of saving seeds. The hands, drawn open in a giving or with a gesture of planting, symbolize the collective effort needed to fight for the right to save seeds and the collective effort to produce food in a sustainable way. However, the disembodied hands can also be read as the disconnect between people and the land or planting traditions.

What do you hope gallery visitors leave thinking about?

While my research and imagery pertain to a specific region in South America, the issues I address are global issues and also lend themselves to comparison with Canada’s – and other countries’ – colonial heritage and agricultural practices. I’m hoping to create an awareness of where our food comes from and under what circumstances it has been grown or raised. As average consumers we can make choices to influence the food business industry. Do we support sustainable and/or local food sources? How does transnational agribusiness affect local populations and farmers? What colonial attitudes do we still have towards people, land, and food production? Through my artwork, I am hoping to turn “matters of fact” produced by the sciences into “matters of concern”, as sociologist and philosopher Bruno Latour says so fittingly, and perhaps inspire viewers to see their world differently.

Exhibition title: Miriam Rudolph: disPOSSESSION

Exhibition dates: until March 18, 2017

Venue:FAB Gallery (1-1 Fine Arts Building)

Gallery Hours: Tuesday to Friday 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.

Saturday 2 – 5 p.m.

Admission: Free

![]() Previous articleGovernment Inspector – Video RoundupNext article

Previous articleGovernment Inspector – Video RoundupNext article![]() Angela Snieder: Obscura

Angela Snieder: Obscura