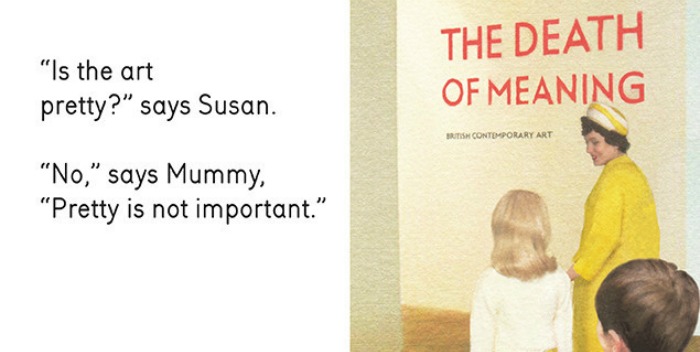

Museums and galleries exist to tell us stories. Why would we go to the gallery if meaning was dead? The image above from Miriam Elia’s satirical book We Go to the Gallery takes a jab at our desire to find meaning and beauty in works of art. By following the children’s experiences in the book, we learn how to think when we visit the gallery.

Do we need to be told how to think when we look at art? The American author Joan Didion writes in The White Album “we tell ourselves stories in order to live.” I think this is true when we look at art, as we often try to figure out what the artist is trying to tell us while we stand in front of their artwork. We search for stories, stories that bring the art and artist to life, stories that make us feel alive.

Our search for stories, or meaning, can project interpretations onto art. This is parodied in the short video Simply Delicious Shower Thoughts with Cookie Monster. It captures Cookie Monster’s reactions to the famous art he sees. While standing in front of Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night, Cookie Monster turns to the camera and remarks, “Hmm, what was the best thing before sliced bread??”

Whether intentional or not, the video mocks the pretensions, and often inaccurate, interpretations people make about art. One of my art history professors once described this practise as “finding pictures in clouds.” In an attempt to connect with an artwork, we find meaning in thin air.

I was told the exact opposite during a recent gallery tour at the Rennie Collection in Vancouver, BC. The docent stated that the “beauty about art is you can never be wrong.” She led the tour by telling us how to think about the artworks, guiding our thoughts with her own interpretations and sharing the insights of the gallery’s owner, Bob Rennie. She periodically stopped her lecture to ask our group what the artwork meant to us. To her, any interpretation was correct, especially one emotionally driven. This is a bit cheeky, but I wish I had remembered some of Cookie Monster’s lines. Something tells me I would have received a thoughtful nod and encouragement for quoting “lobsters are mermaids to scorpions!” I admit, I am being highly critical of this tour. This is because I think it’s destructive to think for others and to confuse meaning with our own feelings about art.

There are such things as right and wrong answers or inaccurate interpretations when it comes to studying anything, especially art history. We bring our own histories and viewpoints to the subjects we study; it’s important to be aware of this bias and to question everything we learn and assert. I don’t think we should be told how to think when we go to the gallery because it minimizes our ability to find answers on our own.

If I had my way, we would be able to touch artwork in galleries. (This would certainly keep conservationists busy!) I don’t like the stiffly enforced separation between the viewer and the artwork. It makes me wonder if the artwork would start to matter less, that it would loose its power over us, if we were able to touch it.

A couple months ago, I visited the Winnipeg Art Gallery, where I was able to pick up a 19th century watercolour and feel the coarse fibre of the paper between my fingers. More than a hundred years ago, an artist held the very same paper and brushed it repeatedly with his paint, capturing one of his many fleeting thoughts. I felt a tactile connection to the artist and his artwork. The watercolour lost its institutionally-imposed grandiosity and became an everyday object, but no less exceptional.

Touching art causes it to seem real and commonplace. It makes me feel comfortable to take my time studying its defining characteristics while I fall for its seemingly insignificant idiosyncrasies. I’m able to interact with, and wade through, my own feelings that are evoked by looking at specific artworks because of this intimacy.

Georges Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières in the National Gallery, London.

We can also form a connection with art by standing face-to-face with it. I did this with Georges Seurat’s painting Bathers at Asnières, which is housed in the National Gallery in London, England. In order to get close to the painting, I had to hold my ground against the pushes and shoves of people posing for selfies in front of the famous work. For what seemed like a long time, I stared at the boy’s red cap, who is standing waist-deep in water on the right side of the image. The cap is a chaos of red and blue dots of paint from up-close. When I stepped backwards, the red and blue dots mingled together to form the cap. I left this painting feeling giddy; for the first time, I saw pointillism up-close. It wasn’t an intimate connection like holding the 19th century watercolour, but the painting nonetheless resonated with me.

My own interests and curiosity guided my interaction with Bathers at Asnières and the 19th century watercolour. This would have been completely different if someone told me how to think when I looked at these works of art. I go to the gallery for these independent, singular experiences. Whether I’m underwhelmed or in awe, I go to think and feel on my own.

![]() Previous articleThe Kaufman Kabaret: Birth control in CanadaNext article

Previous articleThe Kaufman Kabaret: Birth control in CanadaNext article![]() Director’s Notes: The Kaufman Kabaret

Director’s Notes: The Kaufman Kabaret